Rhododendrons, among the Maritime Northwest’s most beloved plants, can vary from two-foot-high dwarf shrubs to 30-foot trees. They are often multi-trunked, or single-trunked but branching into three or more main trunks close to the ground. Most varieties don’t typically need a lot of pruning for their first several years. Some stay compact and tidy; others develop an open habit and need little pruning other than occasional thinning and nipping back of a few wayward shoots.

Over time, many rhodies grow a dense weave of thick-wooded branches, and the thought of pruning one can intimidate all but the most experienced gardener. Of course, we are here to help! Many of the principles of pruning trees and shrubs that we have covered in other blog posts (like Pruning 101) also work for rhododendrons. But rhodies can pose a few unique challenges.

PRUNING BASICS

Let’s start with some basics. Most pruning projects are a combination of thinning and heading cuts. Thinning tends to disperse and often slow down growth. It reduces the density of a plant. It’s best to start pruning with a “clean out” from the inside of the plant, removing branches which are dead, broken, diseased and crossing or chafing each other.

Heading (including pinching and shearing) tends to concentrate and stimulate growth. It increases the density, such as in hedging. The majority of cuts during pruning should be thinning cuts unless you are maintaining a hedge or renovating a tree or shrub by severely cutting back.

For most pruning, leave a minimal stub when you cut off a branch. Don’t leave a long, ugly, dead end branch to die off and attract pests. But also don’t cut it so close as to damage the collar tissue on the mother branch, which it needs to grow over the wound.

Rhododendrons are somewhat unusual in that they will often resprout from cut, bare (living) branches. We describe this advantage under RESTORING below.

To identify whether a bare branch is still alive or dead, make a little scratch in the bark, revealing the thin cambium layer just below. If it's bright green, it's still alive and might still sprout this season. If it's brown, rotting or dry looking, it's dead.

Note that on larger rhododendrons with thicker branches, small hand pruners might be too small for most cuts. For these you may need loppers and pruning saws.

Basic thinning of a shrub: removing random inner branches reduces density while preserving the plant’s shape and character.

WHY PRUNE?

As with pruning any plant, ask yourself these questions:

“Do I really need to prune this plant, and why?”

“What does this plant want to do?”

“What do I want this plant to do?”

Has it become an opaque blob in the center of your garden and you wish to make it a bit more open and treelike? Read about THINNING below.

Is it planted in too small of a space and you want to reduce its size or just head it back a little? …REDUCING may be the answer.

Is it a leggy, sparsely blooming shrub that you would like to develop more leaves and flowers like it used to? …let’s talk about RESTORING.

Note: Just because you’ve always heard that you’re supposed to prune your rhododendron doesn’t mean you’re obligated to do so. Plant maintenance should not be a prescribed, automatic chore, but rather a flexible solution to a specific problem.

TIMING

You can prune a rhododendron almost any time of year without harming it, but the best time is within a few weeks after it has finished blooming, to give it the maximum time to set flower buds for next year. Waiting too late is no disaster, but could mean fewer blooms for the next year (or a few years if you are pruning it back hard). If you’re doing a major restoration with severe cutting back, the best time is late winter/early spring, before the growing season. Beyond that, avoid extremes of hot (over 85ºF) or cold (under 25ºF) for pruning most plants in our area.

DEADHEADING

Independent of pruning you might want to deadhead (snap or cut off spent bloom stalks). We do that to many flowering plants in order to interrupt the energy normally going into seed production and redirect it toward new bloom buds. Also, it visually cleans them up.

Routine deadheading is fine for younger rhodies, but on a large, mature one, it might not make a significant difference for future blooming. Plus, it can take a lot of time! If lower maintenance is a priority, it’s not always necessary to deadhead.

After blooming: deadheading and optional thinning of new sprouts.

Option to thinning new sprouts: cutting bare branches to activate latent buds.

THINNING A DENSE RHODODENDRON

We mentioned the emphasis on thinning to reduce density and reveal a shrub’s natural form, rather than a lot of heading (or shearing). But thick branches, dense foliage and the interweaving tendency of some rhododendrons call for a bit more patience.

Before and after thinning (and slight heading back) of a large rhododendron.

Before and after thinning (and slight heading back) of a smaller, upright rhododendron or azalea.

After the initial cleaning described in BASICS, you can start thinning, as we say, “inside-out, bottom-to-top, small-to-large.” Work from the inside of the shrub, usually at the bottom, randomly pruning off small branches at their base (where they sprout from a larger branch) and work your way up and out. You can also remove some of the lower branches to help the shrub “float” off the ground a bit more. Then start removing redundant branches which grow through the middle of other dense growth, unless they are major structural branches.

After pruning out several of these, step back to see what difference it is making in the density. You might notice larger branches which could also be removed unless it might create large holes in the shrub’s foliage mass. If there are several major branches crowded together, it’s good to thin out the mass.

Dealing with a tangled, weaving branching habit entails cutting one branch at a time and pulling it out of the tangle. As you reduce the density, you might also discover long, flexible branches you don’t wish to cut. You can sometimes “reweave” those out from other branches, helping to open up the shrub’s form.

Before and after thinning of a dense (and somewhat leggy) rhododendron.

Can you start to see through the shrub much more than when you started? If not, keep going. When you have one zone of the shrub that looks sufficiently thinned out, then move on to another zone achieve approximately the same density. You don't want to remove every last tiny branch inside the shrub. Thinning aims to improve the transparency of the plant, not skeletonize it.

After thinning the interior, you might still have an outer “shell” of crowded shoots which emerge from near the tips after blooming. You can thin out the numbers of those new shoots (sometimes they snap right off) or, if things are really crowded, cut some of their parent branches further back.

When you feel the whole shrub feels more open (we like to say that it can “breathe”), and not such a dense blob, you can stop! Always better to prune too lightly in one season, than too severely. We advise to not remove more than 25% of the living tissue in any one year.

REDUCING SIZE

Although heading back outer branches to shorten a plant is easy to understand and seems like a natural way to control the size, it can create a lot of future issues. Some plants tolerate frequent heading just fine, such as common hedging shrubs. But most plants are genetically “programmed” to reach a certain size range at maturity and will expend a lot of growth energy to attain that size.

If you just need to nip back a few long stragglers to clean up your plant, no problem. But if you try to reduce its natural size by more than about 20%, it can react, sending pent-up growth energy into aggressive sprouting. We further describe the risks below.

Shortening a rhody that wants to be much taller often results in a mess of new sprouts!

Rhodies react to heading cuts this way. That can be an advantage when trying to stimulate more leaf growth on a leggy plant, as explained below. But it complicates things if you wish to keep it unnaturally small.

Some rhododendrons can grow into trees 10 feet and higher. If you allow and even train them to reach their potential height through thinning, they can become dramatic, neighborhood landmark trees. There are many wonderful examples in our region, notably at the Rhododendron Species Botanical Garden in Federal Way, and UW’s Washington Park Arboretum.

But an all-too-common situation is a house with a front picture window about five feet above the ground. Years ago, someone (not you, of course!) planted a rhododendron or a group of them under the window for a pretty foundation planting. Either the the information provided by the plant seller suggested the shrub would not grow taller than 6 feet, or that it could grow larger, but that was “after 10 years” or the fine print was ignored altogether. In any case, the rhody is now big and crowding out the window, if not the whole house.

Right plant/wrong place… Reduce size? Remove? Or thin out to become landmark trees?

(photos: L-The Redeemed Gardener, R-The Outlaw Gardener)

Unless you’re willing to significantly thin or remove this giant, the challenge is how to reduce it in a way that doesn’t make the tree look chopped or beheaded. It would be easy to just head it way back, as in REJUVENATING below. But after the initial clearcut, this would likely trigger aggressive sprouting, which can turn it into an even faster-growing, unattractive beast for years to come.

Think instead about redirecting growth energy from the upper leader(s) to lower secondary branches. The method for this is called releadering or drop crotching. Cut a leader branch (tallest one in a branch group) back to a lower side branch (at least half the thickness of the branch you are cutting). Now the lower branch is likely to become the new leader. On a typical rhody there are multiple leaders, so you would releader several of them to shorter branches.

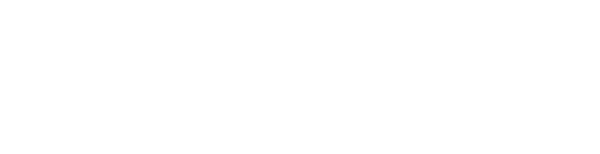

Releadering to gradually reduce height: remove entire branches (rather than randomly heading them back) to transfer the leader growth to lower branches.

On a dense-foliage rhody (or any dense plant), if you shorten all the tallest leaders you will likely open up bare spots — open areas with bare branches and little foliage that were previously shaded out by what you have just removed. In time, these will resprout and fill in but it can take a year or several, depending on the type and vigor of the plant.

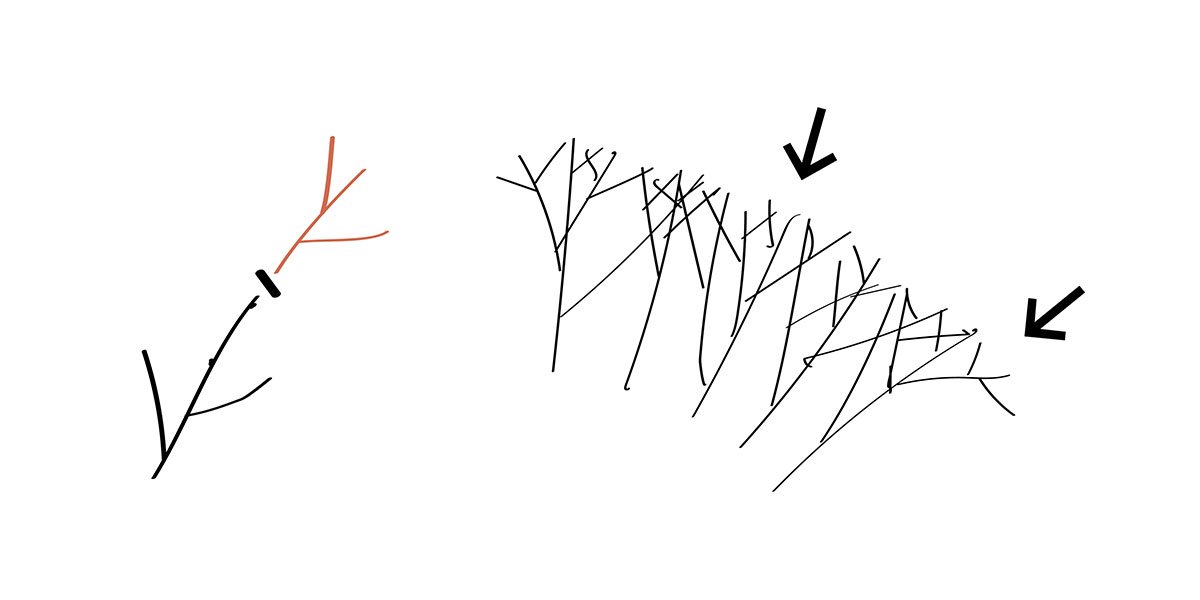

With any major reducing, restoring or rejuvenating, we recommend to avoid (if possible) doing this all at once. If you can spread the job over two or three years you might minimize the bare or chopped look and the overreactive regrowth.

For example, you could do releadering on maybe 1/3 or 1/2 the number of tallest leaders, so the top layer is thinned out but not totally removed. Then after a year or two with the lower layers growing in, you can cut back the rest of the top layer. But remember: it may still react to a major reduction over time. Unnatural pruning creates a high-maintenance plant.

RESTORING A RHODODENDRON

Older rhodies can develop quite a leggy habit, especially after years of being crowded by neighboring plants, struggling under dense trees, or just having aged a long time without any pruning attention. Others may suffer low vigor from poor drainage, depleted soil, or other stresses.

Restorative pruning can make quite a difference, along with improving the watering, mulching, and fertilizing of a struggling plant. If the shrub is heavily shaded (unless it’s possible to thin out overhead trees), blooming might always be sparse. And although these methods can help revive most shrubs, some might have deeper health issues and not sprout as well.

A leggy habit is long, tangled, bare branches with few leaves or flowers out on the tips. Restoring a more balanced branching pattern and redirecting growth energy back into foliage and blooming often takes a combination of thinning, untangling/reweaving, and heading back some bare branches.

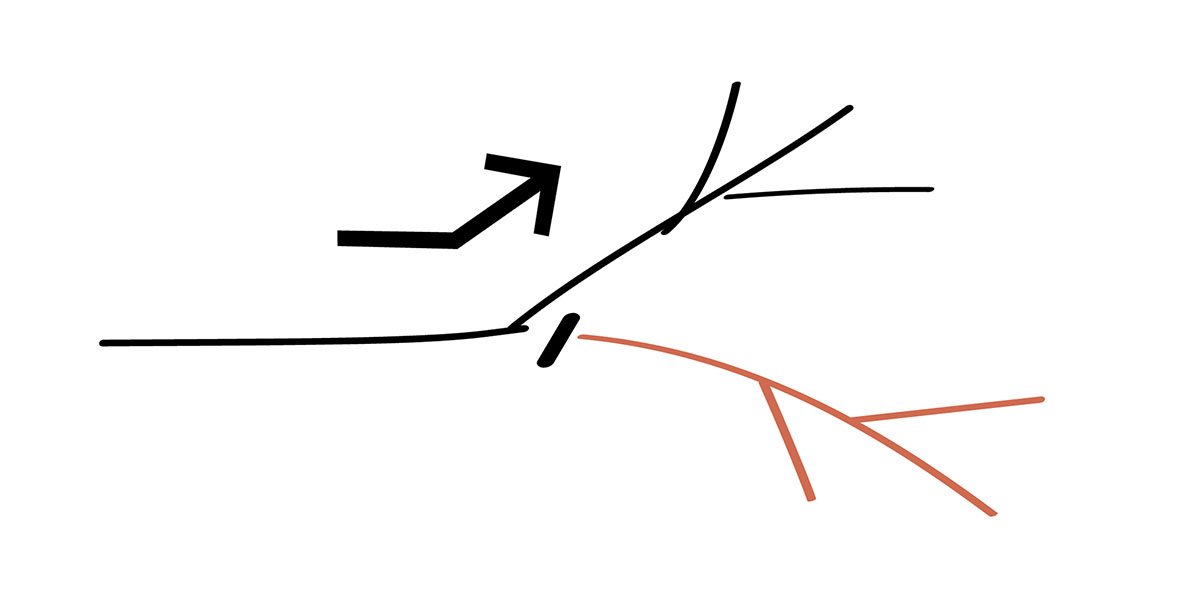

Restoring a leggy rhododendron with thinning and some heading, to encourage more interior growth.

For long bare branches in the interior that are alive (look for leaves at their ends or use the scratch test described under BASICS), remove any that are causing crowding, and perhaps choose a few to head back, to stimulate their latent buds. Live rhododendron trunks and branches are lined with latent buds (conspicuous or hidden) which often “wake up” when the growth above them is removed.

Combination of thinning and heading back bare branches to induce sprouting and reduce legginess.

If you don’t want to cut off a branch you can try “nicking” the bark just above a latent bud (if the bud is conspicuous). Make a small cut with a pruner blade or small saw barely deeper than the cambium layer. This can “fool” the bud into sensing that the whole branch has been cut, activating new growth.

…OR REJUVENATING ONE

If you feel you must rejuvenate (or renovate) one from scratch, cutting it down to a few primary branches a few feet high will, if it is healthy, cause it to sprout and grow quickly. Late winter/early spring is the season for this. Then you can thin and manage the new branches as they develop using the methods we have described here.

Renovating an old rhododendron from the ground up. (C and R photos: ProperLandscaping.com)

Some gardeners might choose this if it’s an unusual, hard-to-find variety or of sentimental value. Again, consider doing this gradually over two or three years rather than one fell swoop. But if it’s not an exceptional plant, weigh this option with the amount of work (and awkward habit) ahead, vs. just replacing it with a new rhododendron.

SIMILAR PLANTS

There are other shrubs that can be pruned in a similar way to rhododendrons. Common examples include Lily-of-the-Valley shrub (Pieris), mountain laurel (Kalmia), Camellia, strawberry tree (Arbutus unedo), and English and Portuguese laurels (Prunus laurocerasus and lusitanica). These, as well as some popular deciduous shrubs such as lilac, mockorange and forsythia, have latent buds which can sprout from bare branches, so most can tolerate occasional hard pruning.

So the pruning methods we have described apply similarly. On dense or overgrown plants, thin out the inner branching structure, manage multiple sprouts, and reduce or restore plants only if necessary.

Once again, don’t prune your rhododendrons just because “you’re supposed to” but in order to address specific problems and let them be healthy and beautiful.

Still have questions? We are always here to answer your care questions on this or any other gardening needs by emailing garden@swansonsnursery.com, via social media, or in person at the store!