Rhododendrons (and azaleas, included in the genus Rhododendron) are well-suited to our maritime climate and popular for their bold, colorful flowers and relatively tidy habits. We have a few PNW natives, including our Washington State Flower! There are several species from the southeastern U.S., particularly the Appalachian Mountains, but most species originate in moist, mountain areas of Asia, and a myriad of cultivars have been developed from these.

Azaleas generally differ from rhododendrons in the following: Most azaleas are smaller shrubs (under 3 feet high). They tend to have finer stems and smaller leaves with fine hairs or fuzz, and some subspecies are deciduous (dropping their leaves in fall). Their flowers have 5-6 stamens (vs. 10 for rhodies) and tend to be smaller and spread out more on the plants, in contrast to the dense, rounded trusses on many rhodies. There are rhodies that seem like azaleas: dwarves, small-leaf types, sparse bloomers, and even a few deciduous species, but most follow the above differentiation.

Rhodies and azaleas are both easy to grow and care for when their basic needs are met.

SUN / SHADE

As most species originate in moist forest habitats, most prefer partial shade (such as morning sun/afternoon shade, or dappled shade under trees). Some species and cultivars (mostly smaller leaf) are sun-tolerant, and others in the PNW can handle full sun with supplemental summer watering. Many also tolerate deep shade, although that can cause minimal flowering and slow, sparse growth.

SOIL

They like moist, well-drained, mildly acidic soil high in organic matter, as in forest settings. They generally don’t do well in dense or compacted soil, and will suffer if soil is constantly wet.

Most have fibrous roots which form a dense mat near the soil surface and don’t tolerate a lot of disturbance. While you can plant groundcovers or other small, shallow-rooting plants beneath a mature rhody, try to minimize the digging needed to plant or weed, to avoid damaging surface roots.

See our Recipe for Planting Success.

WATERING

As they like moisture, consistent watering is essential for the first couple of years, especially during the dry periods of our typical summer and early fall. Established plants need less but appreciate a thorough watering every few weeks during dry periods. Focus on watering the soil over the roots. Try to minimize watering the foliage, which can enable leaf spot diseases, especially during the summer months.

MULCH

To conserve soil moisture and bolster organic matter, top-dressing the root zone with 1 to 2 inches of a compost-based or leaf-based mulch every 1-2 years is helpful. Keep mulch several inches away from the trunks to prevent stem rot (a good practice for almost any woody plant). Natural leaf litter in your garden or low plants which cover the soil around a rhody can serve the same function.

FERTILIZER

Acid-based fertilizer (often labeled for rhodies, azaleas, camellias, and/or conifers) can help get them established and enhance their blooming. This is typically applied a month or two before, and immediately after the bloom period.

PESTS & DISEASES

Healthy rhododendrons have few pest issues, but aphids or root weevils can attack weakened, overly shaded, or dense plants. Aphids can suck on tender new growth, causing curling and sticky residue. Wash them off with blasts of water or consider neem or horticultural oils for persistent cases. Spider mites or lacebugs can also occasionally appear, and treatments would be similar.

Root weevils may chew notches out of leaves in spring and are largely a cosmetic issue. Note that if the notches show mostly brown edges (as in the above photo), the damage is not likely recent. But their larvae can damage roots, which is a larger threat. Again, healthy rhodies aren’t usually affected as much, but if weevils gain momentum, treating the adults (when active) with sprays, or larvae with diatomaceous earth or beneficial nematodes may be needed. Ask us if you suspect a serious infestation.

Diseases are rarely serious, but weakened or stressed plants can exhibit powdery mildew, rust, or bacterial or fungal leaf spotting. Most of the time, removing the worst leaves, keeping up consistent watering (but not overwatering or getting foliage wet), and improving the soil with mulch and/or fertilizer will address the problem. Root rot diseases can be more serious, usually related to the culture and care of the plant. Again, ask us for help with diagnosing these.

COLD / HEAT

Cultivars are rated for hardiness (minimum temperature tolerance). When we get cold snaps below freezing, covering plants may be recommended. If cold enough, many hardy rhodies furl their leaves like cigars, which may look alarming, but is a natural defense mechanism. In most cases, the leaves will unfurl and look normal once temperatures rebound. Extreme or long-lasting freezes can kill, but that’s not common in the Puget Sound region. If some leaves or branches don’t show signs of new growth by late spring, prune them off.

Issues with heat and sun tolerance have historically been minor in our region, but could increase with climate change. The primary effect of sun and heat on rhododendrons is leaf scorch (sunburn). As with other pests and leaf diseases, it’s mostly a cosmetic problem, although some plants did not survive our extreme heatwave of June, 2021. Vulnerable plants can be covered with fabric ahead of time to lessen the solar intensity, and mulching over surface roots can also help keep them cool and moist. But if leaves do show scorch, pull off the worst ones, or wait until the following spring’s new growth to remove the rest.

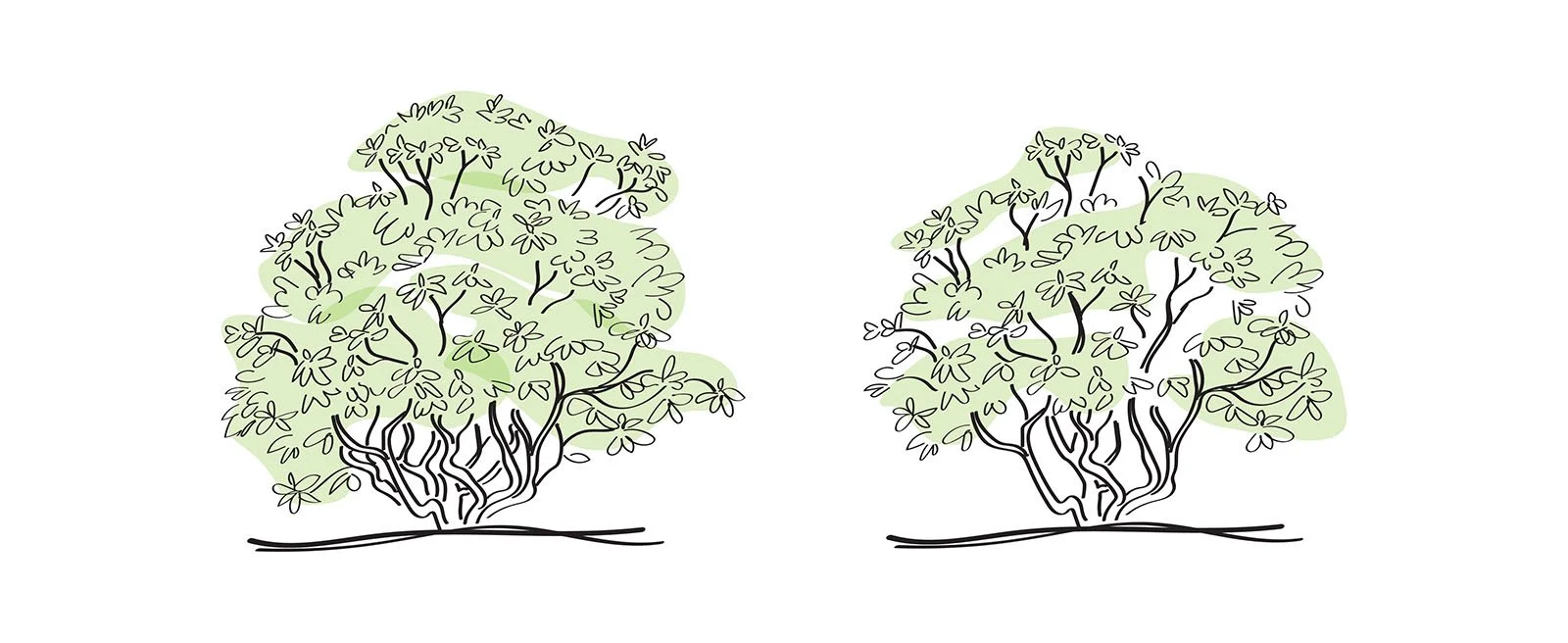

Before and after thinning a rhododendron.

PRUNING

Here are a few basics to keep in mind:

1) It’s nearly always better to thin and open up a rhody shrub rather than cut it back and make it denser. An exception would be an older, leggy plant in need of restoration.

2) If you do any major cutting back, such as to reduce size, do so within a month or two after it blooms. This will give the plant time to regenerate bloom buds for next year. Unlike many woody plants, you can cut a healthy rhody branch back to where there is no foliage, and it will sprout again from latent buds. But we don’t recommend this on a regular basis, because there will be less blooming and an unnatural shape.

3) Deadheading (snapping off spent bloom trusses) redirects energy into next year’s blooms rather than seed production. Also, it visually cleans up the plant. But on a large, mature plant, deadheading takes a lot of time and might not make a big difference in future blooming.

See our blog post, Pruning Rhododendrons, for more detailed information.

TRANSPLANTING

Because rhododendrons have such dense, compact root balls, they tend to tolerate being dug and moved better than many other woody plants. The outer perimeter of an established rhody root ball is often well-defined; digging is typically easy (depending on soil) outside of it, very hard within it.

But keep in mind, the root balls of large rhodies can be quite heavy, requiring strong tools and strong backs. Even small ones can be surprisingly heavy. Recruit some strong friends, and/or take heavy-lifting precautions.

Rhododendrons and azaleas can thrive and look beautiful for a long, long time with the right care. Please contact us if you have any questions!